From 201 BC until around the turn of the 4th to the 5th century AD the Roman legions were the best army in the western world. From Scotland to Egypt and from the Danube and Rhine rivers in the north to the Sahara desert in the south, Roman legions would be stationed in the frontiers to protect from foreign invasion.

The legions got beaten the occasional time but, in general, they would be able to shrug off defeat, learn from their mistakes and succeed where they had failed. Even when repeatedly bested the Romans were lucky enough to have a huge pool of soldiers in their city. After losing almost 200 thousand men in three battles against Hannibal the Romans were still able to resist, albeit in a defensive posture, during the second Punic war until their final victory at Zama in 201 BC.

But when we speak of the «legion» we tend to not make a distinction between the different phases that it underwent. A legionary from the 400BC would have had a hard time recognising a fellow legionary from 30AD, who himself would’ve probably had a hard time recognising the germanic soldiers from 300AD as being part of the legions. the word ‘Legion’ standing for ‘muster’ after all, any soldier recruited into the oficial Roman army would be a legionary (auxiliary forces not withstanding).

The western Roman army went through 3 main phases, plus what I would call a prologue phase and an epilogue phase. The eastern Roman army, on the other hand, would continue evolving for the better part of a thousand years after the west had fallen, well into the medieval and even early renaissance times.

Prologue: the barbarian rush

Despite its self concocted picturesque origin story, the founders of Rome were indeed probably refugees. Less likely it is that they were refugees from the Trojan war as the Romans would claim. That was a later embellishment to try to link them with the greeks they so much admired. Either way, the first inhabitants of Rome were the kind of people for whom «a fresh start» sounded appealing: convicts, ruined peasants, highwaymen, bandits and refugees of all kinds.

This disorganised rabble was seen by the inhabitants of the more respectable cities around them as little more than a group of thugs and, in my view, they probably were. Until the city developed itself and the famous third king of Rome Tullus Hostilius reorganised the army it is most likely that the Romans fought in the barbarian «all charge» style.

The army would charge, all men yelling and running towards the enemy without any effort to remain in formation. Men would keep on fighting until the enemy (or themselves) were exhausted or fled. Very much in the way movies nowadays depict every battle, there would be almost one on one duels simultaneously until one side ran away or both retreated.

Not the most elegant solution, but against the small towns around Rome it probably worked for a while. Against their more developed neighbours in the north bank of the river Tiber it most likely didn’t.

Phase 1: The Roman Phalanx

The northern neighbours were the Etruscans, an advanced culture of traders and farmers that had settled in the north of Italy a few centuries before, probably migrating from the Anatolian plateau in modern Turkey.

The Etruscan had walled cities, exquisite art and their own developed culture. Later Romans would downplay the influence that the Etruscan civilisation had in Rome, but we find many religious and social customs in the Roman Empire that were not greek, and therefore most probably an Etruscan creation (reading the omens in the entrails of animals, or in the flight of birds just to name two).

By all accounts the Etruscans, despite being a loose confederation of independent cities, had organised armies, probably citizen armies in the same style that most greek states had at the time. Their units also fought using the same tightly packed formation that the greeks used: The phalanx. Phalanxes were armed with spears and would march at a steady pace with their shields held up high maintaining cohesion at all times. Against disorganised mobs a Phalanx would be deadly, mowing down incoming warriors one by one.

The Romans must’ve quickly adapted into the phalanx formation, probably just a few years after the foundation of the city. By the year 650BC the Roman would have had an army of citizens (land owning males) in which every person would have to bring their own equipment. Those rich enough to have an cuirass, spear, greaves, helmet and shield would fight as heavy infantry. The poorer the citizen the less equipment they would be able to provide for themselves, all the way down to the skirmishers who would just bring stones and slings. Soldiers were farmers that would join the army during their campaigning season and then go back to their farm when it was finished or in years of peace. The landless couldn’t join the army, as it was assumed that those that had no property to protect would more easily desert in the thick of the battle. A few of the richest citizens would have enough money to bring their own horse, they were the Celeres «the quick ones», later known as Equites which made reference to not just the military unit but the social class.

The Phalanx was an extremely tough unit from the front, and leaps and bounds ahead of the initial tribal warfare that the Romans had started with. It did have it’s drawbacks though: A Phalanx required discipline and coordination, lots of it. Drilling was essential and it took quite some time for a Phalanx to be battle ready after a march, if a phalanx was attacked before it had completely formed it would rout with surprising ease. Phalanxes were also slow to move and turn, making them relatively weak against faster units that could flank them (Cavalry was usually kept on the wings of armies in order to stop possible flanking units in their tracks). Lastly, the lack of speed and mobility of the phalanx was exacerbated in rough terrain, making them prone to losing formation and opening gaps that could be exploited by the enemy.

But in reasonably flat terrain, with cavalry in your wings to protect you from flanking movements, there was no safer bet than to form your phalanxes and march forward. This formation and battle philosophy served Rome well for a few hundred years.

Sometimes though, you don’t have the luxury of flat terrain, or of an enemy army that actually wants to line up their army and fight you «fair and square». Enter the Samnites.

Phase 2: triplex acies, the manipular legion

In 343 BC the Romans and the Samnites began hostilities in what we call now the first Samnite war. The Samnites were mountain people from central Italy, in the Apennine mountains. The Romans managed to provoke them into war thinking that there would be much profit to be had. At least in the initial rounds they were quite wrong.

Samnium was a rough territory, with plenty of mountain passes, valleys, forests and dead ends. The Romans were repeatedly caught in a guerrilla warfare flat footed, some of their greatest defeats in the early stages of the Republic come from their wars against the Samnites. Not only that, but their Phalanxes had trouble forming and marching in the broken terrain of the mountains, making even pitched battles hard to win.

In a show of two-facedness, the Romans would complain about the Samnites not presenting battle while they themselves would lie through their teeth to avoid losing and army that had fallen into a trap.

It is unclear at what stage of the three wars agains the Samnites the Romans changed their old phalanx formation for their new maniples, but by the end of the war the Romans had completely reorganised their battle formation:

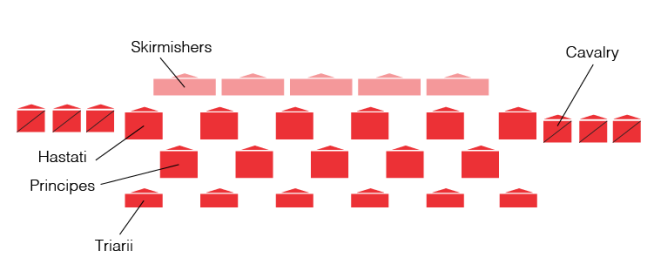

The infantry was divided into three melee groups: The hastati, the principes and the triarii. The hastati were the youngest and least equipped of them, but they were also eager to prove themselves. They carried a sword, shield and, if they had enough money, a helmet and cuirass. The principes were middle aged men, veterans that would be slightly better equipped, in the battle formation they would line up behind the hastati. Finally we have the triarii, older veterans, armed with spears instead of swords. They would be the third and final line of defence and the only unit that would still keep a phalanx type formation.

Each of the three types would be divided into 20 maniples of 120 men each (except the triarii who had only 60 men per maniple). During marches and before engaging the enemy in battle the maniples would march as separate groups. They would create a checkerboard formation while marching towards the enemy and only when they engaged would they close the ranks, forming a closed front. The Hastati would be the first ones to engage the enemy, while the other two groups would wait behind. If they weren’t able to break the enemy, they would slowly start to retreat through the gaps in the checkerboard formation from the Principes, who would in turn take the front to relief them. After a while the same process would be repeated with the principes slowly giving way while the rested Hastati would charge again. The triarii would be waiting in the back and would join the battle just if the hastati and principes started to retreat.

Apart from changing the way units were deployed in respect to one another, the manipular system also changed the inner structure of the units. As stated above, only the triarii remained as a tightly packed spearmen unit. The hastati and principes would be armed with short swords instead of spears, their formation would also be much looser, leaving close to a metre of space between men, both to the sides and to the front and back. The formation would close up when encountering the enemy to have the same advantages of a phalanx, but the spacing between men would permit much more manoeuvrability when charging, as well as making rough terrain less difficult for the formations to negotiate while keeping their cohesion.

As well as being more nimble in the thick of battle maniples had the added value of being much more reactive. Each maniple would have a commanding officer that could order the soldier around where the enemy was pressing harder. This alone was a competitive advantage against other non-reactive units like phalanxes, where the conditions of formation made it almost impossible for the unit to react to new elements in the battlefield; Once a phalanx was committed, it would push forward until the enemy broke. A maniple could shift from one flank to another or be redeployed as needed.

The manipular legion conquered Italy for the Romans, then Carthage, Spain, Greece and the western end of modern Turkey (which the Romans called Asia). The flexibility and strength of the legions would allow them to outflank slower forces, resist in the battlefield longer than less disciplined enemies and adapt to any changes in battle.

Phase 3: Cohorts and landless mules

by 107BC the Roman army was victorious almost everywhere, but it was still a citizen army in the old style, with only landowners allowed to join. Throughout the centuries a ‘compensation’ for the soldiers that had to stay for longer than the usual campaigning season had been introduced but it was still too low and many of the soldiers would get back to their farms after serving their time and find them in ruins. Many a retired soldier had to sell their farm to rich landowners and as the land accumulated in the hands of fewer people more and more dispossessed ended up in Rome and other cities as beggars or even slaves.

Gaius Marius, the consul for that year, found himself in dire straits to get enough land owning men to levy his new army. He had to go north to fight the Cimbri and the Teutones, two marauding germanic tribes that had beaten already a consular army the year before. The Romans were dead scared of the barbarians from the north, still traumatised from the sacking of Rome in 390BC by the gallic warlord Brennus, they were more than happy to give Marius full powers to recruit his army in any way he saw fit.

Marius decided to completely discard the notion of having to be a landowner to join the army. He opened the door to anyone that wanted to join the army, he would equip them, train them, and give them a salary. Marius effectively created the first professional army. As a side note, only Roman citizens could join the legions but the auxilia, other units in the army like archers, light cavalry, or even different types of infantry, could join the army and would receive the Roman citizenship as a discharge bonus. Having a professional army meant that Rome didn’t have to levy and train an army every time an enemy appeared. Their battle hardened veterans would be ready and willing all year round.

The other huge change that Marius introduced to the army (state sponsored unified equipment) had a twofold goal in mind: Firstly, to make sure anyone regardless of income, could join the army. Secondly, and here lies the genius of Marius, he included all the necessary tools for a soldier to survive during campaign away from supplies. Soldiers would also have to carry their own armour and all equipment by themselves. This meant an army didn’t depend on a baggage train anymore, making them much more mobile, less dependant on supply lines and battle ready no matter how far away from friendly territory they were.

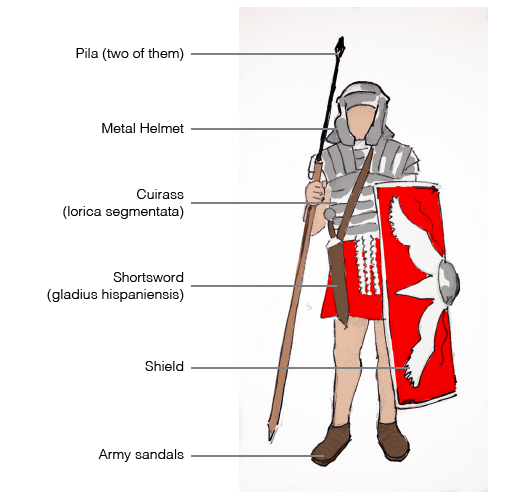

The amount of equipment a legionary had to carry (two javelins, armour, helmet, sword, two sets of sandals, clothes, a cooking pot, a knife, flint, shovel, pickaxe and food supplies for two weeks) earned them the friendly nickname Marius’ mules. Enemies most likely didn’t find the name as amusing as the Romans did.

Marius also got rid of the triple maniple distinction, all legionaries would be equipped equally now. That meant and army wouldn’t become unbalanced if too many soldiers of a particular unit were killed or deserted, any other unit could fill in for them. Furthermore, supplying an army became much simpler. On the other hand, the proven qualities of the previous manipular organisation were kept when possible: Soldiers still marched in a checkerboard formation to the front and kept loose spacing between themselves until encountering the enemy, they would also keep units nimble and reactive by having commanding officers that would have the authority to move a unit around the battle if the circumstances changed. The organisation of the units was slightly changed (bigger units but also more organised subdivisions up to the smallest 8 men contubernium) but the main structure remained.

A side effect of opening the doors to any Roman citizen was the shifting of the loyalty of the army from «Rome» as a common ideal and origin to generals. Roman citizens could come from any corner of the Mediterranean, most of Rome’s inhabitants were Roman citizens but that doesn’t mean that most Roman citizens were from Rome proper. Most of Latium (the area in Italy around Rome) had been given the Roman citizenship just a few years prior, and some cities around the conquered territories had been given citizenship as well. Citizens had the right to vote if they were in Rome (unlikely if you lived miles away) as well as some tax breaks and, of course, the right to join the legions. On top of that, the base yearly payment a soldier would receive has just about enough to make ends meet, the only way to make some extra cash was plundering. That meant soldiers would end up being more loyal to a charismatic and successful commander than to the politicians in Rome. Less than two decades after the marian reforms a Roman army marched against its mother city for the first time (by far not the last).

Epilogue: Cavalry and germanisation

The marian mules remained as the main infantry force until the fall of the western Roman empire five centuries later. However less and less Romans were willing to join the army after centuries of peace; there was a tendency to make use of the northern barbarians (germanic tribes mostly) as the main force in the empire. Both as cavalry (in the auxilia), as legionaries, and finally in their own units with their own tribal leaders. By the end of the empire the Roman army was more a mercenary group than anything else. Rebellions became more common, since every army was loyal to money and nothing else. The reasons for the decline are complex and and long, but by the fall of Rome the legions were long gone.