In the year 371BC the Spartan army was unexpectedly defeated by the Thebans in the battle of Leuctra. The Spartans had been beaten before, but never in a pitched battle against an enemy of similar numbers. Their hoplites (very heavy infantry) were rightfully considered the elite by everyone in Greece.

But, how did the Thebans manage to beat them against all odds? We will need to go a little deeper into hoplite tactics and equipment to explain that.

Ancient Greek hoplites were the heavy infantry of choice for everyone. Those with enough money would regularly hire them as mercenaries, and the only way to stop a hoplite unit was to outnumber them in order to attack them in the flanks and rear or to have your own hoplites to challenge them head-on. Everyone and their dog knew than matching a less armored unit against hoplites would be nothing more than throwing them to a meat grinder, so other soldiers were understandably reluctant to follow orders that would pit them against a unit of Greek mercenaries.

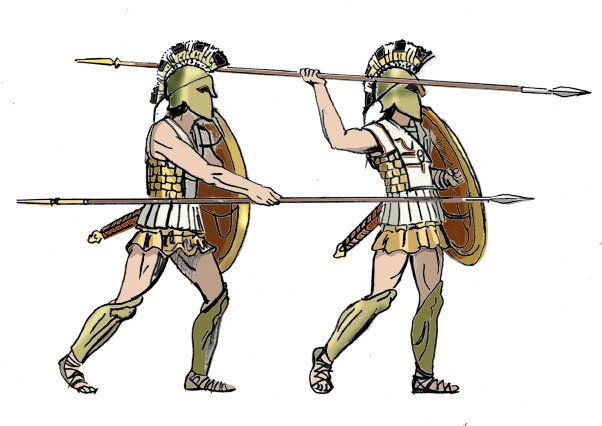

What made them so damn good at their job was their equipment, formation and discipline. They would fight shoulder to shoulder, wearing greaves, helmets, cuirasses and carrying their huge shields (Hoplons) and a spear about 2 meters long. In battle the hoplites would raise their shield and spears in a tight formation 8 to 12 men deep, only the first 3 or 4 lines would actually be able to reach the enemy with their weapons, however the men behind were important for bracing and pushing. The hoplite wall would start marching and charge the enemy, once engaged they would push forward while thrusting their spears. The sheer pressure of 200 odd men in heavy armor pushing a less heavy unit backwards would normally be enough to make the enemy infantry waver and start losing their cohesion. Once that happened the hoplite wall would be able to pick the fleeing enemies one by one or let the cavalry mow them down once they were broken.

Even against vastly superior numbers the only way through a hoplite wall was throwing a better hoplite wall against it. The 300 Spartans (and four thousand Thespians) famously bogged down an army that was probably 30 times bigger at Thermopylae. The Greeks knew better than to hope to beat hoplites with anything that wasn´t your own hoplites and within the Greek world everyone knew the Spartans were the very best. This was an accepted fact, saying there was any better infantry than hoplites and that the Spartiates weren’t the best ones was just wrong.

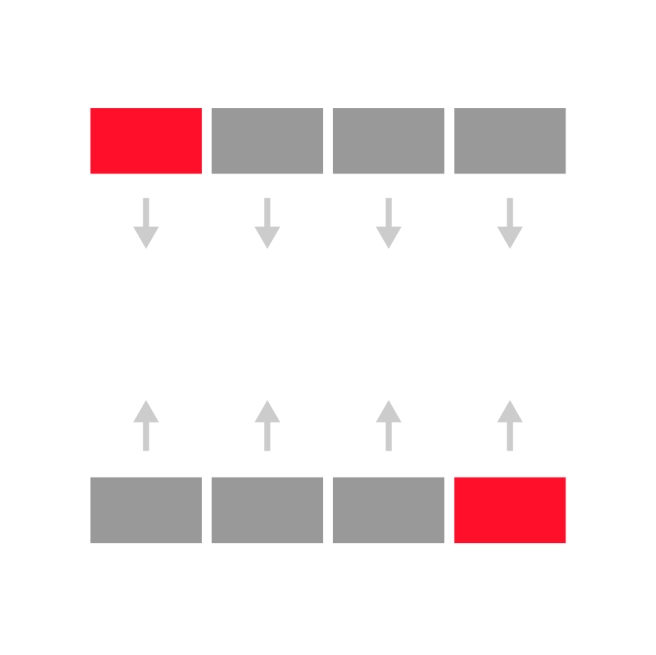

Hoplite forces had also a natural tendency to drift right when marching; soldiers would hold their shield with the left arm, covering the left part of their body and being covered on the right side by the shield of their companion to the right-hand. In such circumstances the natural reaction is to instinctively remain as close to the shield to your right, in order to avoid a gap between shields forming. If every person in a unit tends to push to the right in order to remain under cover the unit will quickly start charging diagonally. In battle this could lead to gaps opening between units, exposing the soft flanks of the formation for the enemy to exploit.

To avoid this Greek armies would usually present a front with their best and most seasoned units on the right flank: Being the most experienced they would be able to control the tendency to drift to the right better and prevent the whole army drifting since less experienced units would be “stopped” in their drift by the straight marching right flank. Again, this was the accepted battle tradition, and everyone expected everyone else to do it because “that’s the way things were”.

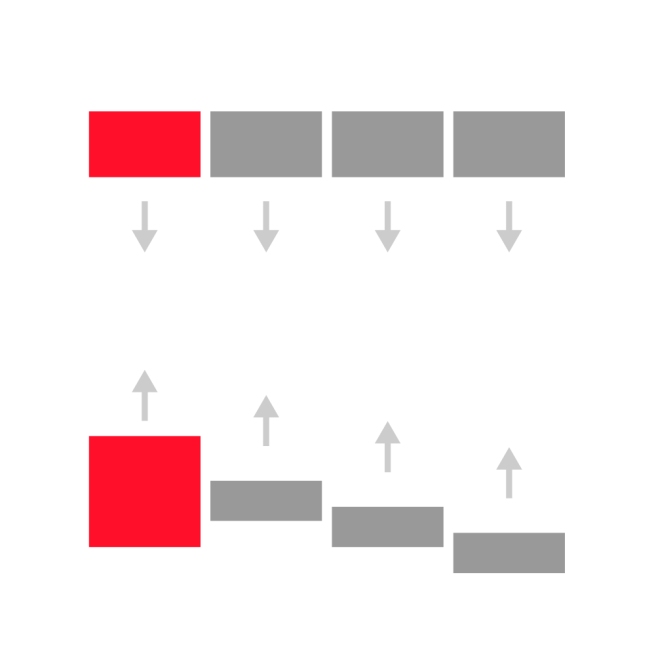

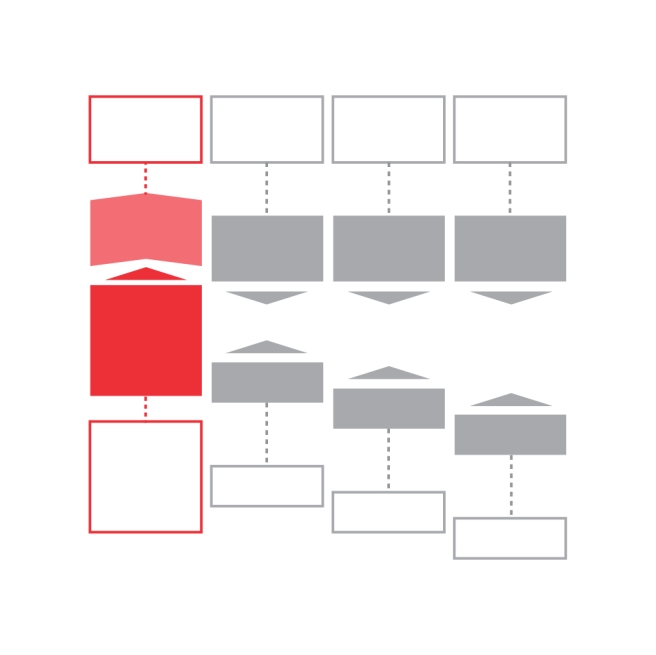

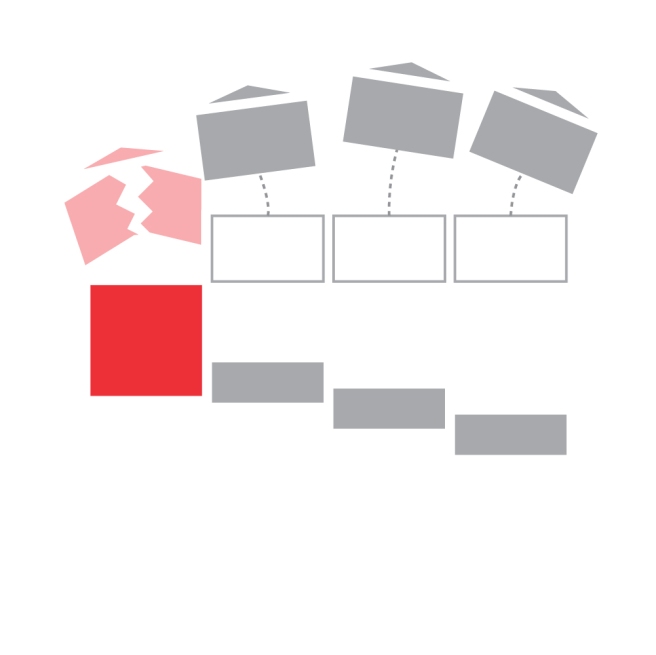

Epaminondas, the Theban commander, counting on the Spartans to follow tradition (not a risky bet at all, the Spartans were notoriously conservative) decided to mass his best soldiers on the left flank instead, while placing his other units further back the more to the right they were, effectively creating a echelon formation and making sure the first forces that met were the main Spartan force against his own crack troops. He also massed his cavalry on the left flank and created a 50 man deep formation for his Hoplites on the left, instead of the common 8 to 12 deep formation.

The Spartans, completely oblivious, settled for a classic flat front with themselves as the elite troops on the right and their Peloponnesian allies on the left. As soon as the two fronts met the Theban’s 50 deep phalanx managed to break the thinner Spartan line and rout them. The Spartan allies, who still hadn’t engaged the Thebans thanks to Epaminondas echelon formation, turned back and left the battlefield without fighting as soon as they saw the main Spartan unit beaten.

The defeat proved to be a turning point for the balance of power; No longer were the Spartans the undisputed masters of the Peloponnese and most of the cities in the north of the peninsula rose in revolt against Spartan dominance along with the Messenians, the inhabitants of the region immediately due west of Sparta.

Sparta would never again rise to be the hegemonic power in Greece, their predisposition to superstition and adherence to their ancient rules would prevent them from ever reinventing themselves. Their short lived empire after their defeat of Athens in the Peloponnesian war was a one off experience and the Spartans decided to revert to their traditional isolationism.

The deeper formation that had soundly beaten the Spartans was further developed in the next decades by king Phillip II of Macedon, father of Alexander the Great, who at the time was a hostage of sorts in the Theban Polis and probably had first hand experience of the training of the Theban army and of the battle itself. Phillip would give his hoplites a much longer spear, slightly lighter armour and smaller shield. His pikemen phalanxes would steamroll the whole of Greece and the Persian Empire in the hands of his son Alexander, who famously never lost a battle. The pikemen phalanx remained the most powerful infantry unit in the ancient world in the Greek successor kingdoms until the Romans beat them using the manipular system, but that is a story for another day.